People turn to Kava (a traditional Pacific‑Island beverage made from the roots of Piper methysticum) for anxiety relief, but the conversation often stalls when liver health enters the picture. If you’re wondering whether you can safely combine kava with prescription meds, how the extract type changes risk, or what monitoring looks like, this guide walks you through the science, the red flags, and practical steps to protect your liver.

Key Takeaways

- Water‑based kava extracts carry far less hepatotoxic risk than ethanol or acetone extracts.

- Kava inhibits cytochrome P450 (a family of liver enzymes that metabolize most drugs), so mixing it with CYP3A4, CYP2C9, or CYP2C19 substrates can raise liver enzyme levels.

- High‑risk scenarios include heavy alcohol use, pre‑existing liver disease, high daily doses (>300 mg kavalactones), and genetic polymorphisms of metabolizing enzymes.

- Regular monitoring of ALT, AST, and bilirubin is essential when kava is used alongside other meds.

- Regulators in Europe and Australia have restricted organic extracts; in the U.S. they remain available as a dietary supplement with strong safety warnings.

What Is Kava and How It Works?

Kava contains a group of compounds called kavalactones (the active constituents that produce sedative and anxiolytic effects). When consumed, kavalactones bind to GABA‑A receptors, producing calming effects similar to benzodiazepines but without the same addiction potential. Traditional Pacific cultures prepare kava as a water‑based decoction, which extracts mainly the kavalactones and leaves behind most non‑polar constituents.

Western markets often sell kava as capsules, teas, or tinctures. The extraction method matters: organic solvent extracts (ethanol, acetone) pull out additional lipophilic compounds that have been linked to liver injury. This distinction underpins most of the safety debate.

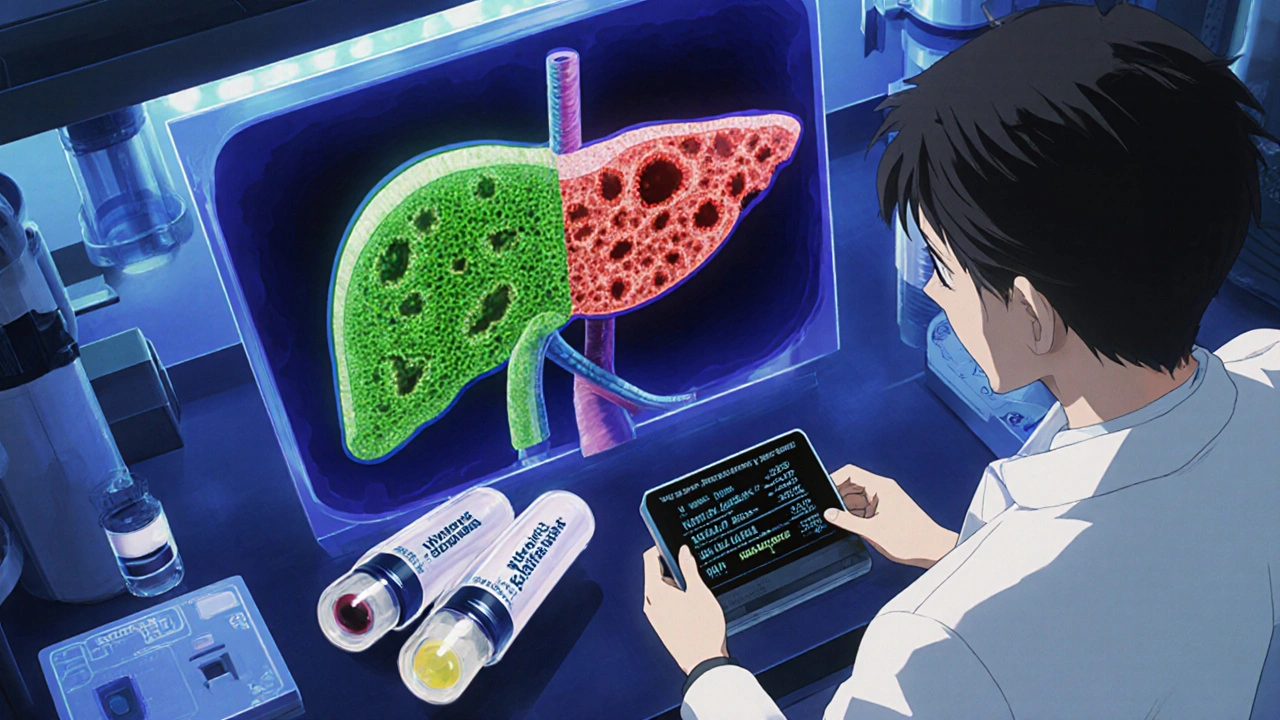

Why Liver Health Matters with Kava

The liver is the body’s detox hub, relying on cytochrome P450 enzymes to break down drugs, herbs, and toxins. Kava can deplete glutathione, the liver’s primary antioxidant, and directly inhibit several CYP isoforms, especially CYP3A4, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19. When these pathways are blocked, other medications linger longer, and toxic metabolites accumulate, raising the risk of hepatotoxicity (liver injury that can progress to failure).

Clinical case reports illustrate the danger. One NCBI LiverTox case described a patient taking 240 mg kavalactones per day alongside hormonal contraceptives, a triptan, and acetaminophen. Within 16 weeks, ALT spiked to 2,442 U/L (normal < 17 U/L) and bilirubin reached 40 mg/dL, necessitating liver transplantation.

Extraction Methods and Their Risk Profiles

Understanding how kava is prepared helps you assess risk. Below is a quick comparison of the two most common approaches.

| Factor | Water‑Based Extract | Organic Solvent Extract (Ethanol/Acetone) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary compounds extracted | Kavalactones, minimal non‑polar constituents | Kavalactones + flavokawains + other lipophilic molecules |

| Typical kavalactone dose per serving | 60-120 mg | 150-280 mg |

| Hepatotoxicity reports (2000‑2024) | Rare - <5 documented cases worldwide | High - >30 confirmed cases in Europe and Switzerland |

| Regulatory status (U.S.) | Allowed, marketed as “traditional” kava | Subject to FDA warning letters |

| Interaction risk with CYP enzymes | Moderate inhibition | Strong inhibition (CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19) |

When you see “kava extract” on a supplement label, look for the extraction method. If it’s not water‑based, treat it as a higher‑risk product.

How Kava Interacts with Common Medications

Because kava competes for the same metabolic pathways, the biggest danger lies with drugs that rely heavily on CYP3A4, CYP2C9, or CYP2C19. Below are the most frequently cited classes:

- Statins (e.g., atorvastatin) - increased plasma levels can trigger muscle toxicity.

- Anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin) - altered metabolism may amplify bleeding risk.

- Antidepressants (e.g., sertraline, fluoxetine) - combined CNS depression and unpredictable serum concentrations.

- Antiepileptics (e.g., carbamazepine) - reduced clearance may lead to toxicity.

- Oral contraceptives - case reports show heightened liver enzyme elevations when combined with kava.

- Acetaminophen - both deplete glutathione, creating a perfect storm for liver injury.

Even over‑the‑counter sleep aids that contain diphenhydramine can become problematic because they are also metabolized by CYP2D6, which kava can inhibit to a lesser extent. The safety rule of thumb: if a medication lists CYP3A4, CYP2C9, or CYP2C19 as a major pathway, avoid kava or consult a healthcare professional.

Identifying High‑Risk Situations

Not all kava users will develop liver problems, but certain factors dramatically raise the odds:

- Extraction type - organic solvent extracts are the single biggest red flag.

- Dosage - daily kavalactone intake above 300 mg increases injury risk.

- Alcohol consumption - alcohol also stresses glutathione stores.

- Pre‑existing liver disease - hepatitis, fatty liver, or cirrhosis magnify toxicity.

- Genetic polymorphisms - variations in CYP enzymes can make a normally safe dose hazardous.

- Concurrent hepatotoxic drugs - especially acetaminophen, certain antibiotics, or high‑dose statins.

When two or more of these boxes are checked, the safest move is to stop kava altogether.

Monitoring and Safety Strategies

If you or a patient decide to try kava, set up a monitoring plan before the first dose.

- Baseline labs: order ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin.

- Follow‑up testing: repeat labs at 4‑week intervals for the first three months.

- Symptom checklist: watch for fatigue, dark urine, yellowing of skin or eyes, abdominal pain, or unexplained nausea.

- Dose titration: start with the lowest water‑based dose (e.g., 60 mg kavalactones) and never exceed 200 mg per day without medical supervision.

- Alcohol restriction: avoid alcohol entirely while on kava.

Should ALT rise above three times the upper limit of normal (ULN) or bilirubin exceed 2 mg/dL, discontinue kava immediately and re‑evaluate the medication list. In most reported cases, liver function normalizes within weeks after stopping kava, unless there’s severe injury requiring transplant.

Regulatory Landscape and Market Trends

Regulators have reacted differently around the world. The European Union banned kava‑containing products in 2002 after a cluster of liver injury reports. Australia classifies kava as a prescription‑only medicine; you need a doctor’s order to obtain it legally. In the United States, kava remains a dietary supplement, but the FDA issued a 2020 Scientific Memorandum warning about hepatotoxicity, especially with organic extracts.

The market continues to grow despite the warnings. Grand View Research estimated the global kava market at $1.12 billion in 2022, with North America accounting for roughly 35 % of sales. The American Botanical Council reported an 18 % sales increase in 2021, driven largely by anxiety‑focused consumers. However, sales of “traditional water‑based” preparations are a niche segment, and many consumers cannot easily differentiate product types from label language.

Future regulatory moves may focus on standardizing extraction methods rather than outlawing kava outright. The WHO’s latest review urged manufacturers to label the extraction process clearly and to limit kavalactone content to ≤250 mg per day for water‑based products.

Bottom Line for Users and Clinicians

Here’s the practical take‑home:

- If you need anxiety relief and have a healthy liver, choose a certified water‑based kava product, keep the dose under 200 mg kavalactones per day, and avoid alcohol.

- Never combine kava with drugs that are metabolized by CYP3A4, CYP2C9, or CYP2C19 unless a physician approves intensive monitoring.

- Patients with any liver disease, regular alcohol use, or on statins, warfarin, antidepressants, or acetaminophen should skip kava entirely.

- Set up baseline and periodic liver labs. Discontinue at the first sign of enzyme elevation.

- Ask your pharmacist or doctor about the extraction method. If the label is vague, treat it as a high‑risk product.

By staying informed about the type of kava you’re using and how it interacts with other meds, you can protect your liver while still enjoying the calming benefits that many people find valuable.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take kava with my blood pressure medication?

Most blood pressure drugs are metabolized by CYP3A4 or CYP2D6. Because kava can inhibit these enzymes, the safest approach is to avoid concurrent use or to have your doctor monitor blood pressure and liver enzymes closely.

Is a tea made from kava root safer than capsules?

Yes, if the tea is prepared with water only. Water‑based tea extracts the kavalactones without pulling out many of the lipophilic compounds linked to liver injury. Capsule products that list ethanol or acetone as part of the extraction process are higher risk.

How often should I get liver tests while using kava?

Start with a baseline panel, then repeat every four weeks for the first three months. If enzymes stay normal, you can extend testing to every three months, but stop immediately if any symptom of liver trouble appears.

What dose of kava is considered safe?

For water‑based products, most experts recommend not exceeding 200 mg of kavalactones per day. Doses above 300 mg have been linked to a higher incidence of hepatotoxicity, especially when combined with other drugs.

Why do some countries ban kava while others allow it?

The bans usually target organic solvent extracts, which have a clear record of liver injury. Countries that allow kava often require it to be marketed as a traditional, water‑based product or keep it behind a prescription barrier to limit misuse.

10 Comments

Anurag Ranjan October 25 2025

If you stick to water‑based kava and keep your dose under 200 mg kavalactones per day, the liver risk is minimal.

Pair it with regular ALT/AST checks and you’ll stay safe.

James Doyle November 7 2025

Understanding the pharmacokinetic interplay between kava’s kavalactones and cytochrome P450 isoforms is essential for any clinician navigating anxiolytic adjuncts.

First, the aqueous extraction yields a phytochemical profile dominated by lipophilic‑poor kavalactones, which exhibit moderate inhibition of CYP3A4, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 compared to solvent‑based extracts.

Second, ethanol or acetone extraction co‑extracts flavokawains and other non‑polar constituents that act as potent, irreversible inhibitors of the same enzymatic pathways.

Third, the dose‑response curve demonstrates a threshold effect around 300 mg of total kavalactones per day, beyond which hepatocellular injury incidence climbs sharply.

Fourth, concomitant administration of drugs metabolized by these isoforms-such as statins, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and anticoagulants-leads to elevated plasma concentrations, increasing both efficacy and toxicity risks.

Fifth, the depletion of hepatic glutathione reserves by both kava and acetaminophen compounds the oxidative stress, precipitating a cascade of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Sixth, genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C9*3 or CYP3A5*1 alleles can exacerbate these interactions, rendering some patients ultra‑sensitive.

Seventh, longitudinal monitoring protocols recommend baseline liver function panels followed by 4‑week interval assessments for the first quarter of therapy.

Eighth, any ALT elevation exceeding three times the upper limit of normal should trigger immediate cessation of kava and a comprehensive medication review.

Ninth, regulatory guidance across the EU and Australia reflects a precautionary approach, restricting solvent‑based extracts while allowing traditional aqueous preparations under strict labeling.

Tenth, clinicians should counsel patients on abstaining from ethanol to avoid synergistic hepatotoxicity.

Eleventh, the therapeutic window for anxiolysis without significant hepatic compromise appears optimal in the 60–120 mg kavalactone range per dose.

Twelfth, patient education materials must explicitly state extraction method, dosage, and potential drug–herb interactions.

Thirteenth, pharmacists play a pivotal role in intercepting high‑risk combinations at the point of sale.

Fourteenth, future research should focus on standardized biomarker panels to predict individual susceptibility.

Fifteenth, until such precision tools are validated, a conservative prescribing ethos remains the safest path.

Finally, integrating these evidence‑based safeguards ensures that kava’s calming benefits can be harnessed without compromising hepatic integrity.

Edward Brown November 19 2025

They don’t tell you that the pharma lobby manipulates the data to keep kava off the market.

ALBERT HENDERSHOT JR. December 1 2025

From a clinical perspective, the safest approach is to verify that the supplement label specifies a water‑based extraction, initiate therapy at the lowest effective dose, and schedule liver function tests every four weeks for the first three months. This protocol aligns with both hepatology guidelines and patient‑centered care, ensuring that any early signs of hepatocellular stress are caught before irreversible damage occurs. 😊

Suzanne Carawan December 14 2025

Oh sure, because mixing liver‑stressors always ends in a spa day.

Kala Rani December 26 2025

People love to hype kava as a miracle cure but forget that the solvent extracts pull out the nasty stuff.

Stick to tea and you’ll dodge most of the drama.

Lionel du Plessis January 7 2026

Kava’s pharmacodynamics are interesting especially when you consider the CYP450 inhibition profile, but in the real world most users just want a chill vibe without the liver drama.

Andrae Powel January 20 2026

I’ve seen patients who thought “a natural product must be safe,” only to develop elevated transaminases after a few weeks of high‑dose solvent‑based kava. A gentle reminder: baseline labs, low dosing, and open communication with your prescriber can make the difference between benefit and harm.

Leanne Henderson February 1 2026

It’s great that you’re exploring alternatives for anxiety, but remember: the extraction method matters a lot! If you can, choose a traditional water‑based brew, keep the dose under 200 mg kavalactones, and avoid alcohol while you’re on it. Regular liver check‑ups every month for the first three months are a smart move, too. Staying proactive will keep the benefits without the risks.

Megan Dicochea February 14 2026

When you read the label, look for “water‑extracted” or “traditional preparation.” Those words usually mean the product contains the safer fraction of kavalactones. If the label mentions ethanol or acetone, consider it a red flag and look for another brand. A quick chat with your pharmacist can also clarify any doubts about the extraction process.