There’s a lot of confusion online about affirmative consent and medical decision-making. You might have heard the term in news stories about campus policies or #MeToo reforms-and assumed it applies to doctors, hospitals, or family members making treatment choices for someone who can’t speak for themselves. It doesn’t. Not even close.

What affirmative consent actually means

Affirmative consent laws were never designed for healthcare. They were created to redefine sexual consent in educational and legal settings. Starting in 2014, California passed Senate Bill 967, which required colleges to adopt a "yes means yes" standard: consent must be clear, voluntary, ongoing, and can be withdrawn at any time. Since then, 13 other states have followed with similar rules for sexual activity on campuses and in public spaces.These laws focus on one thing: preventing sexual assault by requiring active, verbal, or physical agreement between people engaging in intimate contact. They don’t mention doctors. They don’t mention hospitals. They don’t mention family members deciding for an unconscious relative. And they never will.

Medical consent works completely differently

When a patient can’t make their own medical decisions-because they’re unconscious, severely confused, or a minor-the system doesn’t ask for a "yes" in the moment. It doesn’t demand ongoing verbal confirmation. Instead, it uses something called informed consent and substituted judgment.Informed consent means a doctor must explain:

- What the condition is

- What the treatment does

- What the risks and benefits are

- What other options exist

- What happens if nothing is done

- Whether the patient is able to understand and agree

This isn’t a form you sign and forget. It’s a conversation. And if the patient is unable to participate in that conversation-say, after a stroke or during an emergency-the law steps in with a backup system.

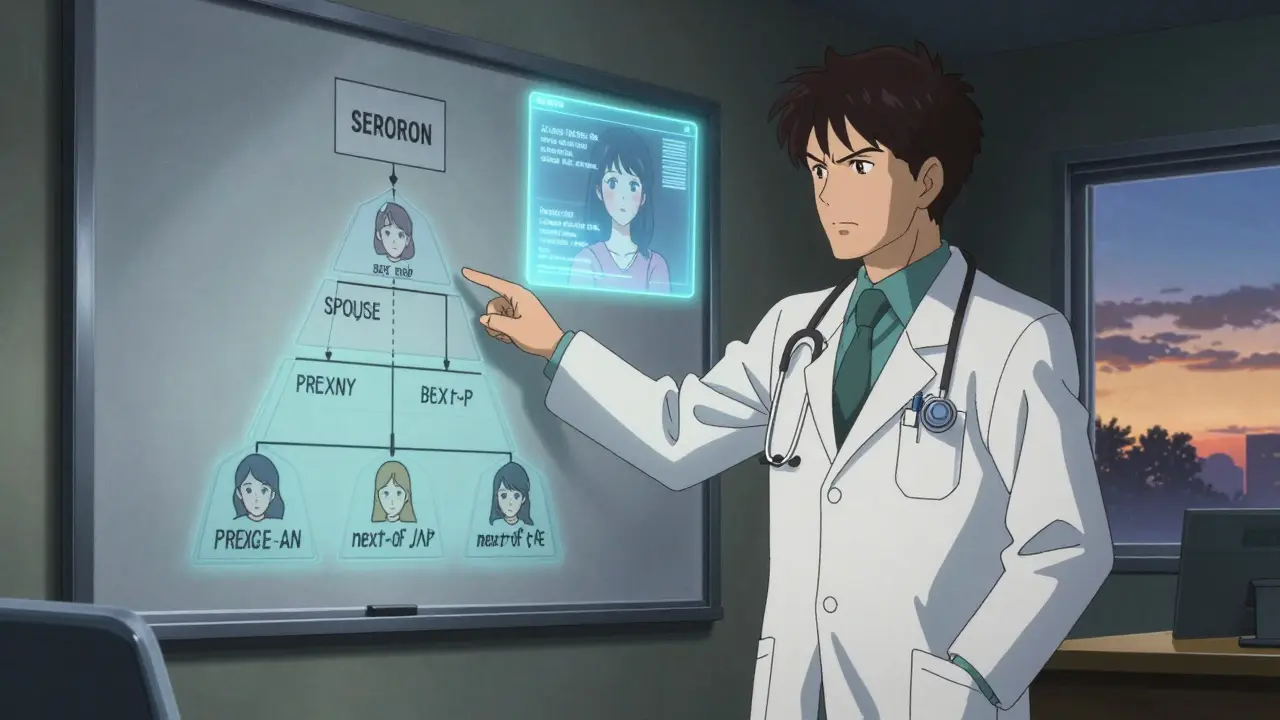

How substitution works in medical care

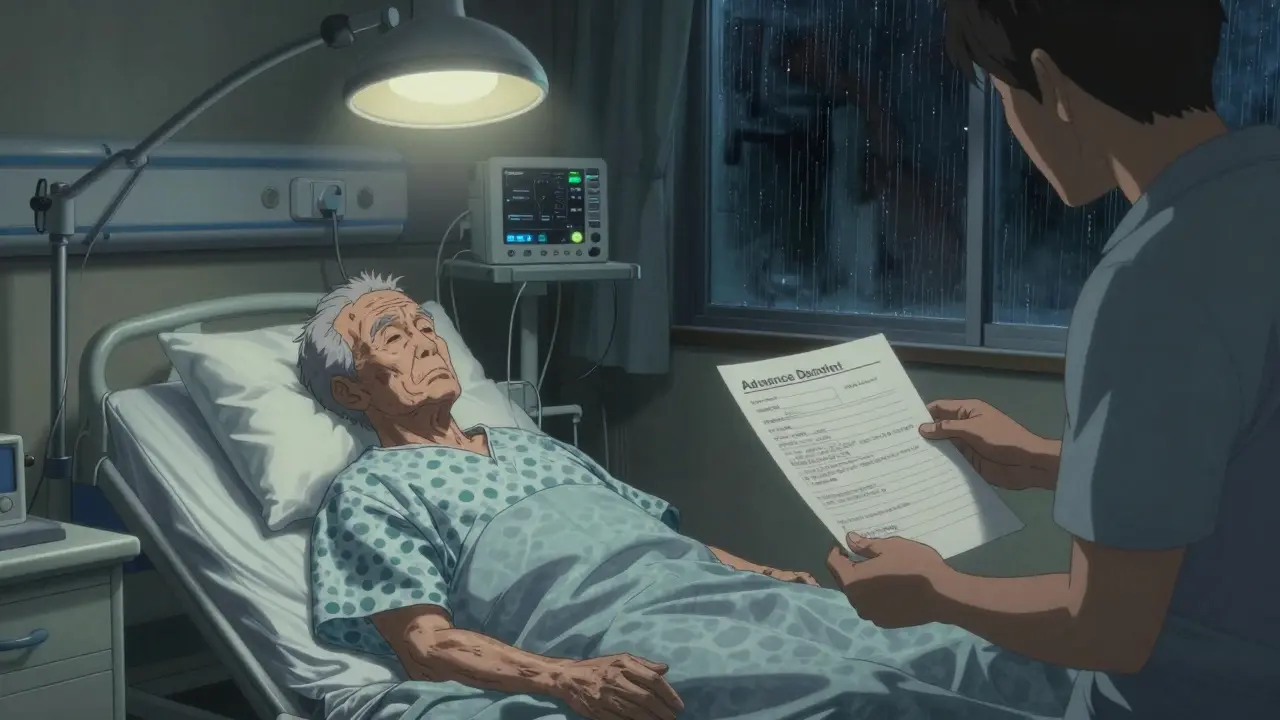

When a patient loses decision-making capacity, the law doesn’t let just anyone decide. It follows a strict order:- First, check for an advance healthcare directive-a legal document where the patient already wrote down their wishes, sometimes even naming a decision-maker.

- If there’s no directive, a legally appointed healthcare proxy or durable power of attorney for healthcare takes over.

- If no proxy exists, the next of kin usually steps in, following state-specific hierarchy: spouse, adult children, parents, siblings.

But here’s the key: the surrogate isn’t supposed to decide what they think is best. They’re supposed to make the decision the patient would have made, based on what they know about the patient’s values, beliefs, and past statements. That’s called substituted judgment.

For example: if a patient told their family 10 years ago they never wanted to be kept alive on a ventilator, and now they’re in a coma, the family can’t say, "I think the doctors should try everything." They’re legally and ethically bound to honor what the patient would have chosen.

Why you can’t mix the two systems

People often think, "If we need a clear yes for sex, why not for surgery?" But the goals are totally different.Sexual consent laws are about preventing coercion in personal relationships. Medical consent is about protecting autonomy in a power imbalance where the doctor holds expertise, access to life-saving tools, and control over information.

Imagine if every time a doctor needed to give antibiotics for pneumonia, they had to ask, "Do you want this?" every 15 minutes while the patient was on a ventilator. Or if a parent had to verbally confirm consent for their child’s appendectomy every time a nurse walked into the room. That’s not patient care-that’s dangerous chaos.

Medical ethics and law recognize that patients can’t always speak, but their choices still matter. That’s why we have advance directives, proxies, and substituted judgment. They’re not perfect, but they’re designed to honor the person’s autonomy-even when they can’t say a word.

What happens if no one knows what the patient wanted?

Sometimes, there’s no advance directive. No family member has any idea what the patient would have chosen. In those cases, the law shifts to the best interest standard.This means decisions are made based on what a reasonable person would choose under similar circumstances. For example:

- If a 90-year-old with advanced dementia has a treatable infection, doctors will usually treat it-it’s low-risk and improves quality of life.

- If that same person has end-stage cancer and is in constant pain, aggressive interventions like intubation might be avoided.

There’s no "yes" required here. No ongoing affirmation. Just a careful, documented judgment based on medical facts and ethical guidelines.

Real-world examples of confusion

A 2023 survey at the University of Colorado Denver found that 78% of undergraduate students couldn’t tell the difference between affirmative consent for sexual activity and medical consent for treatment. That’s not surprising-both use the word "consent." But they’re like comparing a fire alarm to a smoke detector. Both save lives, but they work in completely different ways.Reddit threads like r/medschool are full of medical students asking, "Is affirmative consent required for surgery?" The top answer always says: "No. That’s for sexual misconduct policies. Medical consent is about disclosure and capacity."

Even some hospitals have struggled with this. In 2022, a California hospital briefly trained staff to use "yes means yes" language when asking patients about procedures. It caused panic. Nurses didn’t know how to handle patients who were sedated. Families thought they had to chant "yes" to approve a blood transfusion. The hospital quickly reversed the policy after the state medical board issued a warning: "Applying sexual consent standards to medical care creates legal risk, delays treatment, and misrepresents the law."

What you should do instead

If you care about controlling your medical care-even if you can’t speak for yourself-here’s what actually works:- Write an advance healthcare directive. It’s free. You can do it online in under 20 minutes.

- Name a trusted person as your healthcare proxy. Talk to them. Make sure they know your values-not just your medical wishes.

- Keep a copy in your phone, with your primary doctor, and give one to your proxy.

- Update it every few years, or after major life changes: divorce, diagnosis, loss of a loved one.

That’s how you ensure your voice is heard-even when you’re silent.

Why this matters now

As the population ages and chronic illnesses become more common, more people will face decisions about life support, feeding tubes, resuscitation, and palliative care. The last thing we need is for families to be confused by pop-culture terms like "affirmative consent."Medical decisions aren’t about getting a loud "yes." They’re about respecting a lifetime of values, choices, and quiet promises made in moments of clarity.

The law already has tools for this. You just have to use them.

Does affirmative consent apply to medical procedures like surgery or blood transfusions?

No. Affirmative consent laws only apply to sexual activity. Medical procedures use informed consent, which requires doctors to explain risks, benefits, and alternatives. If a patient can’t consent, decisions are made through advance directives or by legally appointed surrogates using substituted judgment or best interest standards.

Can a family member just say "yes" for a patient in the hospital?

Not automatically. The law requires a specific order: first, check if the patient has an advance directive or named healthcare proxy. If not, next-of-kin may decide-but they must act based on what the patient would have wanted, not what they think is best. Simply saying "yes" without knowing the patient’s values isn’t legally or ethically sufficient.

What if I don’t have an advance directive?

If you become unable to make decisions and have no directive, your doctor will turn to your closest family members following your state’s legal hierarchy (usually spouse, adult children, parents). They’ll use the "best interest" standard-making decisions based on what a reasonable person would choose. But without knowing your wishes, they might choose something you wouldn’t have wanted.

Can a doctor override a family member’s decision?

Yes, but only in rare cases. If a family member makes a decision that clearly goes against the patient’s known wishes (e.g., requesting aggressive treatment for someone who previously refused it), the medical team can request a hospital ethics committee review or even petition a court. But they can’t override a decision just because they disagree with it.

Are there any states where affirmative consent applies to medical decisions?

No. Not one. Every U.S. state, including California, New York, and Illinois, keeps sexual consent laws and medical consent laws completely separate. In 2023, the California Supreme Court explicitly ruled that affirmative consent standards apply only to Title IX and education code violations-not to healthcare. Medical boards nationwide have issued similar warnings.

8 Comments

Alexandra Enns January 24 2026

This is such a load of bureaucratic nonsense. You’re telling me a grandma with dementia can’t get a simple IV because no one ‘knows her wishes’? I’ve seen families cry in ERs while nurses wait for a ‘proxy’ to show up on Zoom. The system is broken. We need to let loved ones say ‘yes’ when it counts-not drag out death with legal fine print. This isn’t autonomy, it’s a paperwork funeral.

And don’t get me started on ‘substituted judgment.’ Who the hell remembers what their cousin thought about ventilators in 2012? People don’t live like that. They live, they love, they panic in hospitals. Let families decide. Stop hiding behind ethics committees.

California’s medical board? Please. They’re still using fax machines. If I’m unconscious, I want my sister to say ‘do it’-not some lawyer in a suit quoting case law. This isn’t a TED Talk. It’s a life.

And yes, I know this isn’t ‘affirmative consent’-but you’re missing the point. People aren’t confused about the term, they’re furious about the delay. The law isn’t protecting autonomy-it’s protecting hospitals from lawsuits. That’s the real ‘yes means yes’ here: yes to liability, no to humanity.

Marie-Pier D. January 24 2026

Thank you for writing this so clearly 💙

I’m a nurse in Vancouver and I see this confusion every single day. Families come in quoting ‘yes means yes’ like it’s a TikTok trend and then break down when we explain they can’t just ‘say yes’ for their mom’s chemo.

But the real win? When someone actually has an advance directive. Last month, a 72-year-old man had his paperwork in his wallet. When he coded, we knew he didn’t want CPR. His wife cried, but she said, ‘He told me 15 years ago. I’m not breaking his word.’ That’s the power of planning.

Please, if you’re reading this-do the form. It’s free. It takes 15 minutes. It saves your family from hell later.

And no, it’s not about sex. It’s about love. And love means honoring what someone truly wanted, even when they can’t say it.

❤️

Shanta Blank January 25 2026

Oh honey, let me grab my popcorn. So now we’re policing how people die because someone on Reddit thought ‘consent’ meant the same thing in a bedroom and an ICU? Brilliant. Just brilliant.

Let’s be real-this whole ‘substituted judgment’ thing is a legal fiction. No one remembers what Aunt Linda said about feeding tubes in 2008. She was drunk at Thanksgiving and said ‘I don’t wanna be a vegetable’-but now that’s a court order? Please.

And the ‘best interest’ standard? That’s just code for ‘we’re gonna do what feels easiest for the hospital.’

Meanwhile, nurses are getting trained to say ‘do you consent to this IV?’ to unconscious patients like they’re asking if they want ketchup. I swear to god, if I see one more family chanting ‘yes yes yes’ into a ventilator like they’re at a rave, I’m quitting.

Medical ethics is not a woke slogan. It’s medicine. And medicine needs clarity, not performance.

Also-California. Always first to overregulate everything. Can we please just… stop?

Chloe Hadland January 26 2026

this is so important and i never thought about it this way

my grandma had a stroke and we had no papers and everyone was so scared to make a choice

it felt like we were being punished for not being perfect children

why does it have to be so hard to do the right thing

just write the damn form

it’s not scary

it’s love

and if you’re reading this right now

go do it

i’m serious

your future self will thank you

Amelia Williams January 26 2026

Okay but let’s talk about the real hero here: the advance directive.

It’s free. It’s online. You can do it on your phone while waiting for coffee. No lawyer. No stress. Just you, your values, and a PDF.

And naming your proxy? That’s the most powerful part. Not just who, but talking to them. Like, actually. Not ‘hey when I’m old just do what’s best.’ No. ‘I don’t want to be stuck in a bed with tubes if I can’t recognize my grandkids.’ That’s the stuff that matters.

I did mine last year after my cousin’s dad got sick. We didn’t know what he wanted. We guessed. We argued. We cried. Don’t let that be you.

Also-hospitals that tried to use ‘yes means yes’? I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed. Like, you’re a hospital. You have a duty to heal. Not to perform woke theater.

Do the thing. Write the form. Tell your people. That’s how you win.

And yes, I’m telling you this because I care. ❤️

Viola Li January 27 2026

Let’s be honest-this whole post is just liberal guilt dressed up as medical wisdom.

You act like ‘substituted judgment’ is some sacred principle, but it’s just a legal loophole for people who can’t make up their minds.

And ‘best interest’? That’s just doctors deciding what’s best for society-cutting costs, avoiding lawsuits, reducing burden. Don’t pretend it’s about autonomy. It’s about efficiency.

Meanwhile, families are forced to become legal detectives just to bury their loved ones. And you want us to celebrate this system?

Why not just let next of kin say yes? Why make death a bureaucracy?

And don’t even get me started on ‘advance directives.’ Most people don’t even know what those are. You think a 60-year-old welder in Ohio is filling out forms? Please.

This isn’t protection. It’s punishment.

And you know what? If I’m unconscious, I want my wife to say ‘do it.’ Not a judge. Not a form. Her.

Dolores Rider January 29 2026

Okay but what if the whole system is a lie?

What if the ‘advance directive’ you signed in 2018 is actually stored in some dark server owned by a hospital conglomerate that also owns your insurance?

What if your ‘proxy’ is secretly on a corporate payroll and they’re just waiting for you to die so they can sell your organs to the highest bidder?

What if ‘substituted judgment’ is just code for ‘we already decided you’re too old to matter’?

I’ve seen the emails. I’ve seen the internal memos. They don’t want you to have control. They want you to be quiet. To be compliant. To be a number on a chart.

And now you’re telling people to ‘just fill out a form’ like that’s going to stop the machine?

It’s not about consent. It’s about control.

And they’re using ‘medical ethics’ to hide it.

They’re coming for your body next.

...I’m not paranoid. I’ve seen the documents.

👁️👁️👁️

Jenna Allison January 30 2026

Let me cut through the noise.

Yes, affirmative consent laws DO NOT apply to medical care. Ever. Not in California. Not in Texas. Not in Alaska.

Medical consent is governed by common law, state statutes, and the doctrine of informed consent-NOT sexual misconduct policy.

Here’s what actually matters:

1. If you’re conscious and competent, you get to say yes or no to every single procedure. No exceptions.

2. If you’re not? Then it’s about prior wishes (advance directive) or surrogate decision-making based on your known values.

3. If no one knows your values? Then it’s best interest-what any reasonable person would choose.

That’s it.

The confusion? It’s because ‘consent’ is used in two totally different legal worlds. Like comparing a passport to a driver’s license. Same word. Different rules.

And yes-hospitals that tried to use ‘yes means yes’ in the ER? They got slapped down hard. Medical boards don’t mess around. This isn’t a debate. It’s settled law.

So stop the misinformation. Do the form. Talk to your family. That’s the real power move.

And if you’re a med student? You better know this cold. It’s on Step 2.

Done. ✅