EDKA Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your EDKA Risk

If you're taking SGLT2 inhibitors (Farxiga, Jardiance, Invokana), this tool will help you determine if you might be experiencing euglycemic DKA (EDKA). EDKA is a dangerous condition where blood sugar remains normal but ketones and acid levels rise.

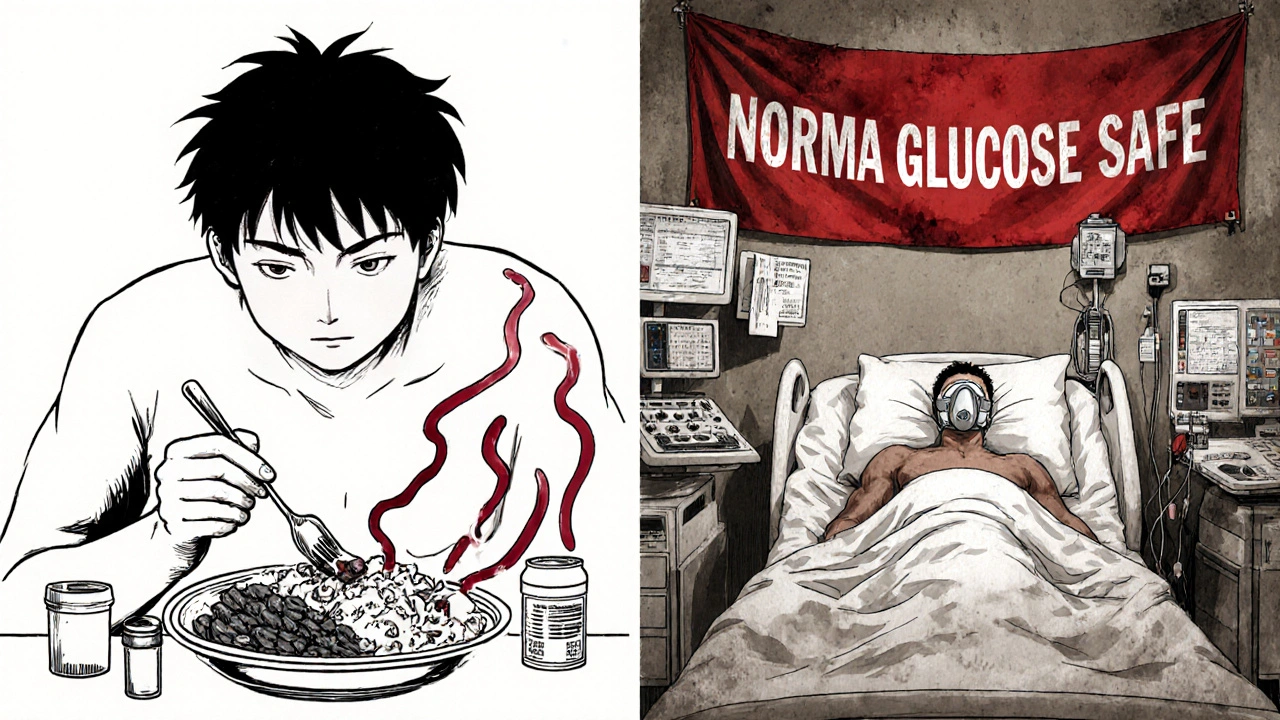

When someone with diabetes takes an SGLT2 inhibitor like Farxiga, Jardiance, or Invokana, they’re often told to expect lower blood sugar, weight loss, and better heart and kidney protection. But there’s a dangerous side effect that doesn’t show up on a standard glucose meter-and it’s killing people who don’t even realize they’re in danger. This is euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (EDKA): a life-threatening condition where the body floods with ketones, acid builds up in the blood, and yet, blood sugar stays stubbornly normal. It’s not rare. It’s not theoretical. And if you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor, you need to know how to spot it before it’s too late.

What Is Euglycemic DKA, Really?

Euglycemic DKA is diabetic ketoacidosis without the high blood sugar. Traditional DKA happens when insulin drops, glucose soars past 250 mg/dL, and the body starts burning fat for fuel-producing toxic ketones. EDKA looks different. Blood sugar stays below 250 mg/dL, often between 100 and 200 mg/dL. That’s not dangerous on its own. But ketones? They’re climbing. Acid levels? They’re spiking. pH drops below 7.3. Bicarbonate falls under 18 mEq/L. And the patient is in full-blown metabolic crisis. This wasn’t well understood until 2015. That’s when doctors in the U.S. started seeing patients with vomiting, abdominal pain, and trouble breathing-but their glucose readings were normal. At first, they thought it was food poisoning or a stomach bug. Then they checked ketones. The results shocked them. All had severe ketoacidosis. All were on SGLT2 inhibitors. The FDA issued a safety alert within months. By 2023, EDKA made up 41% of all DKA cases linked to these drugs, up from just 28% in 2015. Why? Because awareness is growing. But many still don’t test for ketones unless glucose is high. That’s the trap.Why Do SGLT2 Inhibitors Cause This?

SGLT2 inhibitors work by making the kidneys flush out extra glucose through urine. That lowers blood sugar. But here’s the twist: that same action tricks the body into thinking it’s starving. Even if you’re eating normally, your body sees less glucose in the bloodstream and ramps up glucagon-the hormone that tells your liver to make more sugar and your fat cells to break down fat into ketones. Studies show this isn’t just about low insulin. It’s about the ratio of glucagon to insulin. SGLT2 inhibitors increase glucagon, even in people with type 2 diabetes who still make some insulin. That imbalance is what drives fat breakdown and ketone production. At the same time, these drugs cause mild dehydration and reduce the liver’s ability to make new glucose. So you get a perfect storm: ketones rise, glucose stays normal, and the body has no backup plan. It’s not just people with type 1 diabetes. About 20% of EDKA cases happen in people with type 2 diabetes who’ve never had DKA before. Off-label use in type 1 patients is common-around 8% of them are on these drugs-and their DKA risk jumps to 5-12%. That’s why the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology now warns against starting SGLT2 inhibitors in anyone with a history of DKA.How Do You Know If You’re Having It?

Symptoms are almost identical to regular DKA. Nausea? 85% of cases. Vomiting? 78%. Abdominal pain? 65%. Fatigue? 76%. Trouble breathing? 62%. Some people feel like they’re coming down with the flu. Others think they’ve eaten something bad. The biggest red flag? No high blood sugar. That’s the problem. If your meter reads 180 mg/dL, you might think, “I’m fine.” But your blood is acidic. Your organs are under stress. Your kidneys are working overtime to flush out ketones and glucose. Your brain is being poisoned by acetone and beta-hydroxybutyrate. And if you don’t act, you could slip into coma or cardiac arrest. There’s no reliable smell test. The classic “fruity breath” of DKA is often missing in EDKA because ketone levels are lower, but still toxic. Don’t wait for a smell. Don’t wait for a spike. If you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor and you feel unwell, test for ketones-right now.

What Tests Confirm It?

You need three things:- Blood glucose under 250 mg/dL (often 100-200 mg/dL)

- Metabolic acidosis-confirmed by arterial blood gas showing pH below 7.3 and bicarbonate under 18 mEq/L

- Elevated ketones-serum beta-hydroxybutyrate above 3 mmol/L is diagnostic

How Is It Treated in the Emergency Room?

Treatment follows the same basic plan as regular DKA-but with critical adjustments.- Fluids first-0.9% saline at 15-20 mL/kg in the first hour. This fixes dehydration and helps flush ketones.

- Insulin drip-0.1 units/kg/hour. But here’s the key: you can’t wait for glucose to drop before adding sugar. In EDKA, glucose drops fast. So once it hits 200 mg/dL, switch to 5% dextrose in saline. This prevents dangerous hypoglycemia while still letting insulin work on ketones.

- Potassium replacement-65% of patients have low total body potassium even if their blood level looks normal. You’ll need IV potassium, often 20-40 mEq per liter of fluid, monitored closely.

- Monitor for lactic acidosis-some patients have mixed acidosis. Lactate levels must be checked to rule out other causes like sepsis or shock.

How to Prevent It

Prevention is simple-but often ignored.- Stop your SGLT2 inhibitor during illness-if you have the flu, an infection, surgery, or even severe vomiting, stop the drug. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t assume it’s “just a bug.”

- Don’t skip carbs-low-carb diets, fasting, or dieting while on these drugs increases risk. Your body needs fuel. Ketones aren’t a safe backup.

- Check ketones during stress-even if your glucose is normal. Keep ketone strips or a meter at home. Test if you feel off.

- Know your warning signs-nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fatigue, trouble breathing. These aren’t “just symptoms.” They’re alarms.

- Talk to your doctor-if you have type 1 diabetes, ask if SGLT2 inhibitors are right for you. If you’ve had DKA before, they’re not recommended.

12 Comments

Justina Maynard November 29 2025

So let me get this straight-your blood sugar looks fine, but your body is basically fermenting like a bad kombucha? That’s terrifying. I’ve seen people ignore nausea because ‘it’s just a stomach bug’-until they’re in the ICU. This isn’t a glitch. It’s a silent countdown. If you’re on SGLT2 inhibitors, keep ketone strips in your purse like you keep gum. Just in case.

And yes, I’ve had my own scare. No high glucose. No warning. Just exhaustion and a weird metallic taste. I tested. Ketones were 4.1. ER. IV fluids. Three days of feeling like a ghost. Don’t wait for the textbook symptoms. Your meter lies. Your body doesn’t.

Evelyn Salazar Garcia November 30 2025

Another reason to ditch Big Pharma’s latest sugar-coated scam.

Clay Johnson December 1 2025

The body does not mistake pharmaceutical intervention for starvation. It responds to biochemical signals. The real tragedy is not the drug-it’s the reductionist model of diabetes that treats glucose as the sole metric of health. Ketosis is not the enemy. The absence of contextual awareness is.

Jermaine Jordan December 2 2025

This is the most important post I’ve read all year. If you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor and you’ve ever felt off during illness-STOP. TEST. ACT. This isn’t hypothetical. This is survival. I’ve watched someone slip into coma because they trusted their glucose meter. Don’t be that person. Don’t be that doctor. Knowledge isn’t power here-it’s oxygen.

Chetan Chauhan December 2 2025

bro u know SGLT2 inhibitors are just a marketing ploy right? like why would you flush glucose out? that's like throwing money in the toilet and calling it 'weight loss'. also i think this edka thing is just doctors being lazy and not checking glucose properly. my cousin took farxiga and got 'edka' but his meter was broken. he was fine after he switched back to metformin. also why is everyone so scared of ketones? they're natural. i'm on keto and i feel great.

Phil Thornton December 3 2025

My uncle was on Jardiance. Got sick. Thought it was the flu. Didn’t test ketones. Ended up in ICU for 11 days. He’s fine now. But he doesn’t take that drug anymore. And he checks his ketones every time he feels a sniffle. Smart man.

Pranab Daulagupu December 4 2025

High beta-hydroxybutyrate + normal glucose = metabolic red flag. This is why we need better patient education. Especially in non-specialist settings. The science is clear. The protocol is established. We just need to operationalize it. No one should die because a clinician assumed glucose = safety.

Barbara McClelland December 5 2025

Okay, real talk-if you’re on one of these drugs and you’ve never tested ketones before, go buy a meter TODAY. Not tomorrow. Today. Keep it next to your toothbrush. If you’re sick, feverish, or just ‘off,’ test. Even if your sugar is 160. I’ve coached so many patients through this. It’s not scary once you know what to do. You’ve got this. And if you’re a provider? This is now part of your duty. No excuses.

Alexander Levin December 6 2025

They don’t want you to know this. The FDA? Pharma? They profit off your ignorance. SGLT2 inhibitors were rushed. EDKA is being downplayed. They’ll tell you it’s rare. But look at the numbers-41% of cases now. That’s not rare. That’s a cover-up. And why do they still sell it? Because you’re still buying it. Wake up.

Ady Young December 7 2025

I’ve been on Farxiga for 3 years. Never had an issue. But after reading this, I bought a Nova StatStrip. I keep it in my gym bag. If I’m feeling weird after a workout or a long flight, I test. It’s not a big deal. 30 seconds. Could save your life. Thanks for the reminder.

Travis Freeman December 7 2025

As someone from India who’s seen both Western and traditional approaches to diabetes-this is a global issue. We need to spread this knowledge beyond English-speaking clinics. In rural areas, people don’t even have glucose meters. Imagine not having ketone strips. We need community health workers trained to recognize these signs. This isn’t just a US problem. It’s a human one.

Sean Slevin December 9 2025

Wait-so we’re saying that a drug designed to lower glucose… causes metabolic acidosis… because it tricks the body into thinking it’s starving? But the body isn’t starving-it’s just being chemically manipulated? So the drug is essentially creating a pseudo-fasting state while you’re eating? That’s… terrifyingly elegant. Like a biochemical paradox. And yet-we’re still prescribing it? And patients are being told it’s ‘safe’? What even is safety anymore? Is it just the absence of immediate death? Or is it the absence of slow, silent, undetected destruction? I need to sit with this.