Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they account for just 10% of total drug spending. That’s not a coincidence-it’s the result of intense price competition that’s squeezing manufacturers dry. In 2025, the U.S. generic drug market revenue dropped to $35 billion, down from $47 billion five years earlier. Meanwhile, companies like Teva lost $174 million despite $3.8 billion in sales. Meanwhile, others like Viatris held on with slim 4.3% margins. This isn’t just a financial hiccup-it’s a systemic crisis threatening the supply of affordable medicines.

The commodity generics trap

For decades, generic manufacturers thrived by copying simple, off-patent pills-like metformin, lisinopril, or amoxicillin. These drugs had no fancy formulations, no complex delivery systems. Just active ingredients and a label. But when dozens of companies can make the same pill, prices crash. Some generics now sell for less than a penny per tablet. Gross margins? Often below 30%, down from 50-60% just 15 years ago.

The problem isn’t just low prices. It’s the cost to get there. Getting FDA approval for a single generic drug (an ANDA) costs about $2.6 million. Building a cGMP-compliant manufacturing facility? That’s over $100 million. And once you’re in, you’re stuck in a race to the bottom. If one company cuts its price by 5%, everyone else has to follow-or lose market share. The result? Many small manufacturers shut down. Others stop producing certain drugs entirely.

That’s how we get shortages. In 2024, the FDA listed over 300 generic drugs in short supply. Some are antibiotics. Others are heart medications. None are profitable to make. As Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard put it: “The market has failed. Companies can’t profitably produce essential medicines, so they don’t.”

The rise of complex generics

Not all generics are created equal. Some drugs are incredibly hard to copy. Think inhalers with precise particle sizes, injectables that need sterile fill-finish lines, or patches that deliver drugs through skin over days. These are called complex generics. They require advanced formulation science, specialized equipment, and deep regulatory knowledge.

Because there are only a handful of companies that can make them, competition is limited. That means pricing power. Margins? Often 40-60%. Teva’s growth in 2024 came not from cheap pills, but from specialty generics like Austedo XR for movement disorders and lenalidomide for multiple myeloma. These aren’t just copies-they’re improved versions, with extended-release tech or better stability.

Companies that shifted from commodity to complex generics saw their revenue climb. Teva’s 2024 revenue rose 4% to $16.5 billion. Viatris, after shedding its OTC and API businesses, focused on its core complex generics portfolio and posted 2% operational growth. The message is clear: if you want to survive, you can’t just be a copycat. You have to be a problem-solver.

Contract manufacturing: the new lifeline

Another path out of the profit squeeze? Stop trying to sell your own brands. Start making drugs for others.

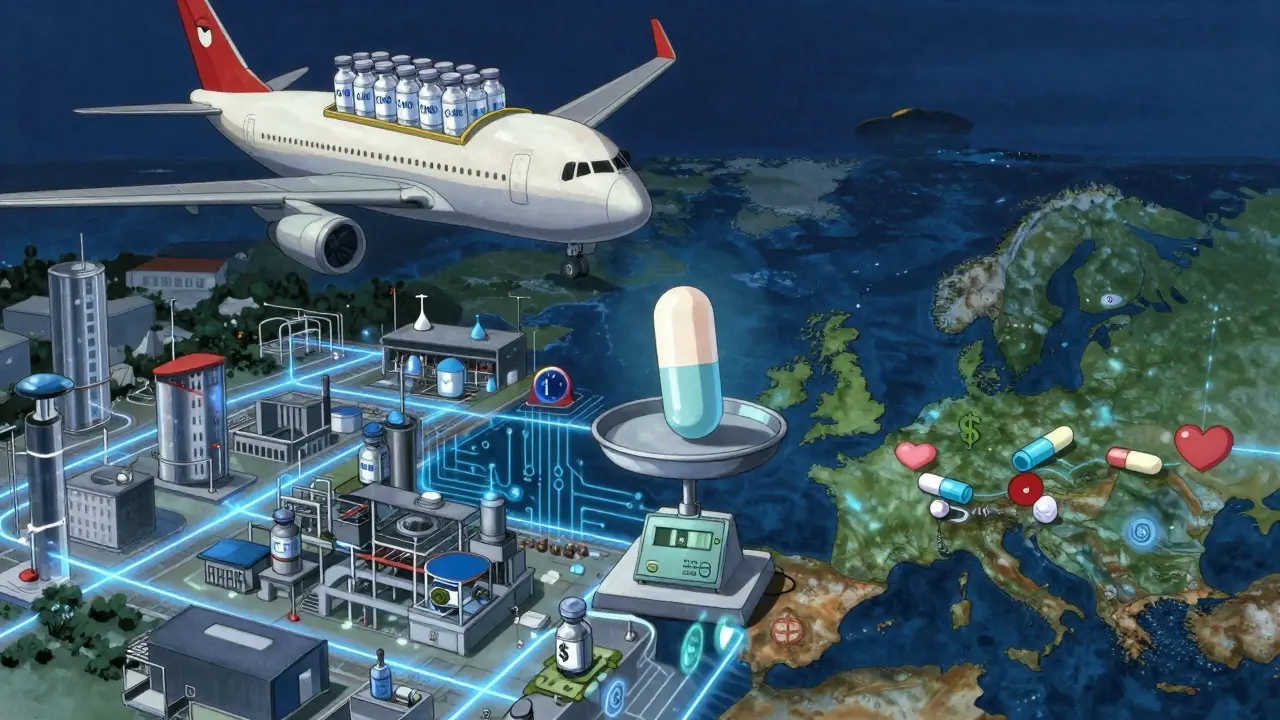

Contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) produce active ingredients or finished products for branded drug companies, generic firms, or even biotech startups. This segment is growing at nearly 10% per year and is expected to hit $91 billion by 2030. Why? Because big pharma doesn’t want to build expensive plants. They want to outsource. And generic manufacturers already have the expertise, the facilities, the regulatory track record.

Egis Pharmaceuticals launched its contract division in late 2023 to serve global partners. Other mid-sized players in India, China, and Eastern Europe are doing the same. These CMOs don’t compete on price per pill-they compete on reliability, speed, and technical skill. A single contract for a complex injectable can bring in tens of millions annually. It’s not glamorous, but it’s stable. And it’s scalable.

Why consolidation isn’t the answer

Many assumed mergers would fix this. And they did-for a while. Between 2014 and 2016, M&A activity jumped from $1.86 billion to $44 billion. Teva bought Actavis. Mylan merged with Upjohn to form Viatris. The idea was simple: bigger companies = more leverage = better pricing.

But it didn’t work that way. Instead of reducing competition, consolidation just moved the battleground. Now, instead of 50 small players fighting over a $10 million drug, you have two giants duking it out. The price still drops. The margins still shrink. And new entrants? They’re scared off. The FDA says over 65% of startups focused on commodity generics fail within two years. Why? They can’t afford the upfront cost, the regulatory delays, or the price wars.

Consolidation didn’t solve profitability. It just delayed the collapse.

Global shifts and regional differences

The U.S. isn’t the whole story. In Europe, generic pricing is tied more closely to production costs and less to PBM negotiations. That means higher margins. In India and China, low labor and raw material costs keep production cheap, even if margins are thin. But those markets come with risks-currency swings, regulatory uncertainty, and intellectual property concerns.

Meanwhile, the global market for generics is expected to hit $600 billion by 2033. Why? Because dozens of blockbuster drugs are losing patent protection between now and then. Humira, Keytruda, and Eliquis are all due to go generic in the next five years. That’s $100+ billion in annual sales up for grabs.

The question isn’t whether demand will return. It’s whether manufacturers will be ready to meet it. The companies that will win aren’t the ones making the cheapest aspirin. They’re the ones building complex delivery systems, mastering sterile manufacturing, or offering end-to-end contract services.

The sustainability question

Can generic manufacturing survive? Yes-but only if it stops acting like a commodity business.

It needs to invest in science, not just scale. It needs to build expertise in formulation, not just fill bottles. It needs to think like a partner, not just a supplier.

For policymakers, the fix isn’t to force lower prices. It’s to reward innovation. Create incentives for companies that make hard-to-produce generics. Fund R&D for delivery tech. Reform the PBM system so it doesn’t punish manufacturers for making affordable drugs.

For investors, the opportunity isn’t in the lowest-cost producer. It’s in the ones with technical moats-those who can’t be easily copied.

And for patients? The stakes couldn’t be higher. If generic manufacturers keep losing money, essential medicines disappear. The system works only if the makers can make a living. Not a fortune. Just enough to keep the lights on-and the pills coming.

10 Comments

lokesh prasanth January 21 2026

Generic drugs are just pills now. No soul. No innovation. Just price wars. Companies dying. Patients suffering. We're treating medicine like toilet paper.

MARILYN ONEILL January 21 2026

I mean, honestly? This is why I don't trust big pharma. They let these companies go bankrupt so they can jack up prices on the new stuff. It's all a scam. I read it on Twitter.

Jerry Rodrigues January 22 2026

The system is broken but not hopeless. People are adapting. Some are moving to contract manufacturing. Others are building tech moats. It's messy. But change is happening.

Jarrod Flesch January 22 2026

Honestly, I'm just glad someone's talking about this 😊 I work in a pharmacy and we're seeing more shortages every month. The complex generics stuff? That's the future. Also, India and China are quietly running the show now 🌏💊

Stephen Rock January 23 2026

Consolidation failed because the players were still playing the same stupid game. You don't fix a broken model by making the losers bigger. You fix it by changing the rules. But nobody wants to do that. Too much work.

Ashok Sakra January 25 2026

Why don't they just make more money? Why is everything always so hard? I don't get it. People need pills. Why won't they just make them and charge more? It's so simple!

Andrew Rinaldi January 27 2026

There's a deeper question here: What do we value more-profit or access? If we want affordable drugs, we have to accept that some parts of the system won't be glamorous. Maybe that's okay. Maybe we need to redefine success.

Gerard Jordan January 28 2026

Big pharma outsourcing to CMOs is the quiet revolution 🤝 India, China, Eastern Europe-they're not just cheap labor. They're skilled partners. The future isn't about who makes the cheapest aspirin. It's about who can deliver the hardest-to-make injectables on time, every time. 🌟💊

michelle Brownsea January 29 2026

This isn't a crisis-it's a moral failure. We've allowed a system where essential medicines are treated like commodities. And now, when people die because they can't get lisinopril, we blame the manufacturers? No. We blame the policymakers. We blame the PBMs. We blame ourselves for not demanding better.

Malvina Tomja January 30 2026

You're all missing the point. The real problem is that nobody has the guts to raise prices. If you can't make a profit, you shouldn't be in business. This isn't charity. It's capitalism. And capitalism doesn't care about your feelings.