Methadone QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

This tool estimates your risk of QT interval prolongation while taking methadone, based on the factors discussed in the article. The results aren't diagnostic but can help you discuss risks with your doctor.

Each factor adds points to your total risk score. A higher score means higher risk of dangerous heart rhythm changes.

Risk Assessment

When you're taking methadone for opioid dependence or chronic pain, the last thing you want to worry about is your heart. But here’s the hard truth: methadone doesn’t just calm cravings-it can mess with your heart’s electrical rhythm in ways that are dangerous, especially when combined with other common medications.

Why Methadone Is Different

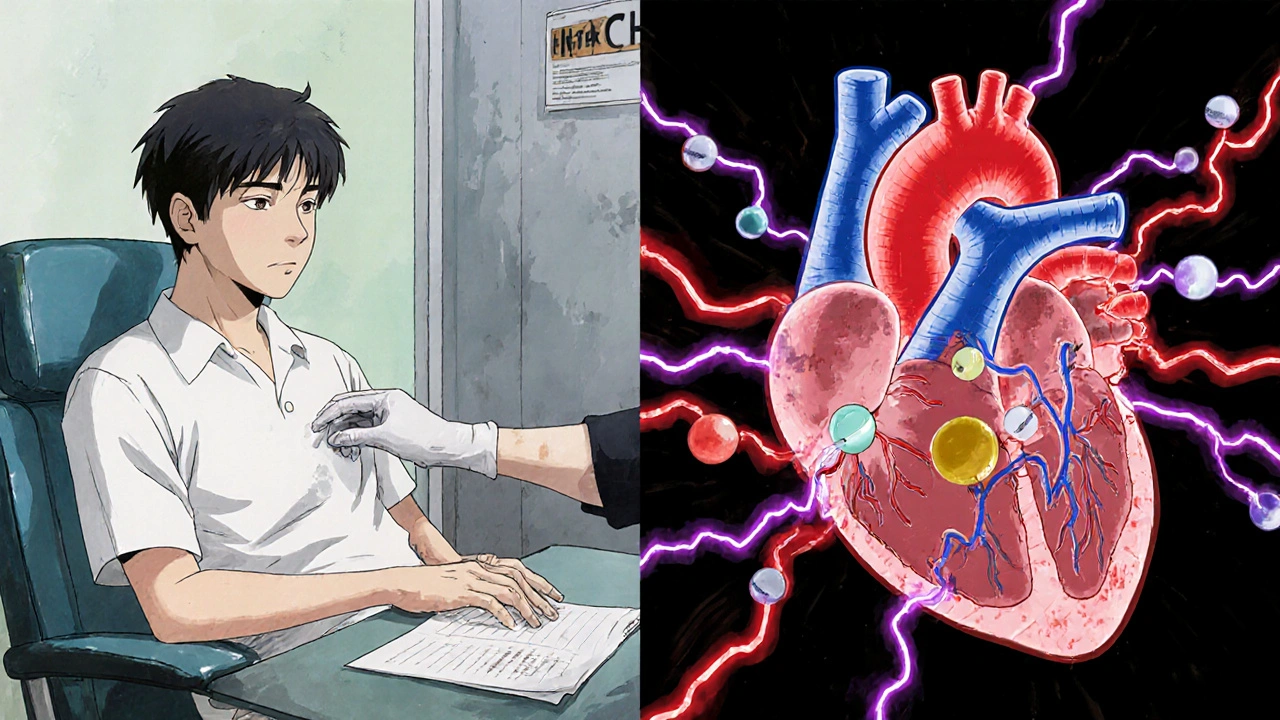

Methadone has been used for decades to treat opioid addiction, and it works. It reduces withdrawal, cuts cravings, and lowers overdose risk. But unlike buprenorphine or other opioids, methadone has a hidden cardiac effect: it blocks two key potassium channels in heart cells-IKr and IK1. Most drugs that prolong the QT interval only hit one of these. Methadone hits both. That’s why even modest doses can cause bigger changes in heart rhythm than expected.The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes the heart’s ventricles to recharge between beats. A normal QTc (corrected for heart rate) is under 430 ms for men and under 450 ms for women. Once it crosses 500 ms, the risk of a deadly arrhythmia called torsades de pointes (TdP) jumps sharply. Studies show that up to 16% of people on methadone maintenance therapy hit that 500 ms threshold-especially at doses over 100 mg per day.

And here’s what’s scary: this prolongation doesn’t happen right away. It builds over weeks. One study tracked patients for 16 weeks and found QTc kept creeping up, even if the methadone dose stayed the same. That means someone might feel fine for months, then suddenly develop a dangerous rhythm without warning.

The Perfect Storm: When Drugs Combine

Methadone alone is risky. But when you add another QT-prolonging drug, the danger multiplies. It’s not just 1 + 1 = 2. It’s more like 1 + 1 = 5.Common medications that can push methadone’s cardiac risk into the red zone include:

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin

- Antifungals: Fluconazole

- Antidepressants: Citalopram, escitalopram, venlafaxine

- Antipsychotics: Haloperidol, ziprasidone

- HIV drugs: Ritonavir (which also slows methadone breakdown, making levels spike)

One case from New Zealand involved a patient on 120 mg of methadone daily who developed torsades de pointes. When doctors dropped the dose to 60 mg, the QT interval returned to normal. Another patient on 150 mg died suddenly at home after years of stable treatment-no prior symptoms, no warning. Autopsy found no structural heart disease. Just prolonged QT.

Even short-term use of these drugs can be dangerous. Cocaine, for example, isn’t prescribed-but it’s a known QT prolonger. A patient on methadone who used cocaine once developed persistent QT prolongation and TdP. The drug didn’t stay in their system long, but the combo was enough to trigger a cardiac event.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on methadone will have heart problems. But some people are sitting on a ticking clock:- Those taking doses over 100 mg/day

- People with existing heart conditions (heart failure, prior arrhythmias)

- Those with family history of long QT syndrome or sudden cardiac death

- Patients with low potassium or magnesium levels

- Older adults, especially women

- People taking multiple QT-prolonging drugs

Women are at higher risk than men-not because methadone affects them differently, but because their baseline QT interval is naturally longer. A QTc of 470 ms might be borderline for a man, but it’s already high risk for a woman.

What Doctors Should Do

Guidelines are clear: don’t start methadone without an ECG. And don’t wait until something goes wrong.Before prescribing methadone, clinicians should:

- Get a baseline ECG for every patient

- Review all current medications-prescription, over-the-counter, and recreational

- Check electrolytes (potassium, magnesium, calcium)

- Ask about personal or family history of sudden cardiac death or fainting spells

After starting methadone, repeat the ECG at 2 weeks, then again at 4 weeks, and then every 3-6 months if stable. If the QTc goes above 450 ms in men or 470 ms in women, monitor more closely. If it hits 500 ms or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline, it’s time to act.

What Can Be Done?

If you’re on methadone and your QT interval is creeping up, you’re not stuck. There are options:- Dose reduction: Cutting methadone from 120 mg to 60 mg can normalize QTc-no need to quit treatment entirely.

- Switch to buprenorphine: Buprenorphine blocks hERG channels 100 times less than methadone. It’s just as effective for addiction treatment and far safer for the heart.

- Correct electrolytes: Low potassium or magnesium makes QT prolongation worse. Simple blood tests and supplements can help.

- Stop or switch interacting drugs: If you’re on citalopram or clarithromycin, talk to your doctor about alternatives. Fluconazole? Try topical antifungals instead.

Some patients worry that switching from methadone to buprenorphine means losing control. But studies show buprenorphine has similar success rates in keeping people in treatment and reducing overdose deaths. The only difference? Much lower risk of sudden cardiac arrest.

The Bigger Picture

Methadone saves lives. It reduces crime, cuts HIV transmission, and keeps people alive when they might otherwise die from overdose. That’s why it’s still used-by the millions-around the world.But safety isn’t optional. The FDA put a black box warning on methadone in 2006 for a reason. We can’t ignore the cardiac risk just because the drug works. The key is awareness, screening, and smart prescribing.

Patients deserve to know: if you’re on methadone, your heart matters as much as your recovery. Ask your doctor for an ECG. Ask if any of your other meds could be making things worse. Don’t assume it’s fine because you feel okay.

Cardiac arrest doesn’t always come with warning signs. But with the right checks, it’s often preventable.

14 Comments

Gary Fitsimmons October 29 2025

Methadone saved my life but I never knew it could mess with my heart like this. Got my first ECG last month and my QTc was 482. My doctor switched me to buprenorphine and I feel just as stable. No more panic attacks about dying in my sleep. If you're on methadone and haven't gotten an ECG yet, just do it. It's one test.

Bob Martin October 29 2025

So let me get this straight. We're giving people a drug that can kill them quietly, then acting surprised when they drop dead at 45? Classic. The FDA warned us in 2006 and we still treat this like it's a suggestion.

Jen Taylor October 31 2025

I'm a nurse in a MAT clinic and I see this every week. One guy on 150mg methadone was also on citalopram and fluconazole for a yeast infection. His QTc shot to 560ms. We pulled the antifungal, lowered his dose, and gave him magnesium. He's alive today. It's not rocket science. Just basic checks. Why isn't this mandatory?

Glenda Walsh November 1 2025

Wait-so if I'm on methadone, and I take a single dose of Tylenol PM, I could die?!!? What about Zyrtec? Or Sudafed? Do I need a blood test every time I get a cold?!!? This is insane. I'm not a lab rat. I just want to feel normal!!

Kevin Stone November 2 2025

People who don't understand pharmacology shouldn't be making decisions about their own cardiac risk. If you're taking methadone, you owe it to yourself to know what you're putting in your body. Ignorance isn't bravery-it's negligence.

Natalie Eippert November 2 2025

This is why America is falling apart. We treat addiction like it's a medical condition instead of a moral failure. Methadone is just a crutch for weak people who can't quit on their own. And now we're giving them free heart monitors? No thanks. Let them suffer the consequences.

kendall miles November 4 2025

Did you know the pharmaceutical companies knew about this for 20 years? They buried the data. The FDA is in their pocket. Even the ECGs are rigged. I know a guy who got his QTc tested twice in one week-different hospitals-different results. They're gaslighting us. This isn't medicine. It's control.

Sage Druce November 4 2025

My cousin was on methadone for 8 years. Never had a problem until she got prescribed azithromycin for a sinus infection. She collapsed at work. They didn't know why until the autopsy. She was 34. If you're on methadone, talk to your doctor. Don't wait for a crisis. Your heart isn't replaceable.

Tyler Mofield November 6 2025

It is incumbent upon the prescribing clinician to adhere to the American Heart Association guidelines regarding QT interval monitoring in patients undergoing methadone maintenance therapy. Failure to do so constitutes a breach of the standard of care and may result in actionable malpractice.

Patrick Dwyer November 7 2025

Switching to buprenorphine isn't surrender-it's strategy. The data shows comparable retention rates, lower overdose risk, and way fewer cardiac complications. If your provider won't even discuss alternatives, find a new one. You deserve care that respects your whole body, not just your addiction.

Bart Capoen November 9 2025

my doc just told me to ‘watch for dizziness’ and called it a day. no ecg. no electrolytes. just ‘you’ll be fine.’ i’ve been on 80mg for 3 years. i feel fine. but now i’m scared to take a cold med. what the hell.

luna dream November 10 2025

They're using methadone to keep us docile. The government doesn't want addicts to get better-they want them controlled. The QT prolongation? A feature, not a bug. It keeps us too tired to protest. Wake up.

Linda Patterson November 11 2025

Why are we even talking about this? The real problem is that people on methadone think they're entitled to special treatment. They don't get to risk their own hearts and then blame the system. Get off the drugs. Stop being victims. Take responsibility.

Shilah Lala November 12 2025

So the solution to a drug that kills your heart is... another drug? Brilliant. Just swap one pill for another. Next you'll tell me we should replace our lungs with oxygen tanks. This is the pinnacle of modern medicine.