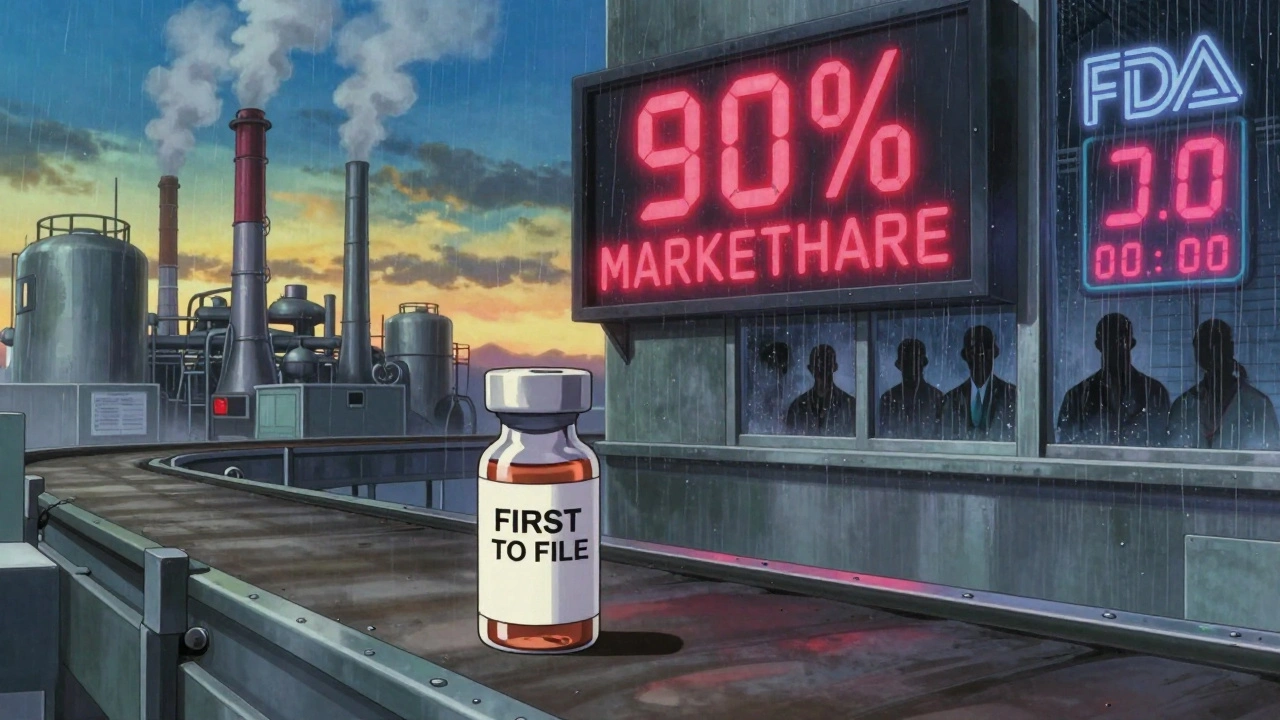

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the race to be the first generic version on the market isn’t just about speed-it’s about locking in decades of revenue. The first company to win that race doesn’t just get a head start. It often captures 90% of the generic market share-and keeps most of it for years, even after competitors arrive.

Why Being First Matters More Than You Think

The U.S. generic drug market didn’t become a $338 billion savings engine overnight. It happened because of a law passed in 1984: the Hatch-Waxman Act. This law didn’t just make it easier to copy expired drugs. It created a powerful incentive: 180 days of exclusive rights for the first generic manufacturer to successfully challenge a patent. That exclusivity window isn’t just a legal loophole. It’s a financial lifeline. During those six months, the first generic faces almost no competition. That means they can set prices close to the original brand’s level-sometimes even higher-because pharmacies and doctors have no other option yet. By the time the second generic arrives, the first one is already stocked in 80% of retail pharmacies, prescribed by 70% of doctors, and trusted by millions of patients. And here’s the catch: once a patient is on a specific generic, they rarely switch-even if a cheaper version appears. Why? Because pharmacists are trained to dispense the same version unless instructed otherwise. Hospitals and insurers prefer to stick with one supplier to simplify inventory. This isn’t about loyalty to a brand-it’s about system inertia.The Real Numbers Behind the Advantage

Data from DrugPatentWatch (2023) shows that the first generic manufacturer typically captures 70-80% of the total generic market during its 180-day exclusivity period. After the second entrant joins, that drops to 50-60%. After five or more generics enter, it settles at 30-40%. Meanwhile, second-place manufacturers rarely break 15%, and later entrants often fight for under 10%. This isn’t random. It’s structural. A study by McKinsey & Company (2023) found that first-movers gain an average of 6-13 percentage points more market share than fair market share would predict. In some cases, like injectable drugs or specialty therapies, that lead jumps to 15-20 points. Why? Because these drugs have fewer prescribers, smaller patient pools, and higher switching costs. For example, a first-mover generic version of a complex injectable for autoimmune disease might hold 85% of the market two years after launch. The second entrant, even with identical ingredients and half the price, might only reach 10%. That’s because doctors won’t switch patients mid-treatment unless there’s a clear safety or cost benefit-and most generics don’t offer either.Who Wins and Who Gets Left Behind

Not all first-movers are created equal. Large pharmaceutical companies with existing generic divisions capture 10+ percentage points more market share than smaller players. Why? They have the infrastructure: multiple API suppliers, FDA-experienced regulatory teams, and relationships with major pharmacy chains. Smaller companies often win the race to file-but lose the war for market share. They may lack the supply chain resilience to handle sudden demand spikes. Or they don’t have the sales reps to convince doctors to switch from the brand. One study found that inexperienced first-movers capture only half the market share of experienced ones, even when they’re first to file. Domestic manufacturers also have an edge. A 2023 NIH study showed that U.S.-based first generics achieve 22% higher market saturation than overseas ones. Why? Faster delivery, fewer supply chain delays, and stronger trust from U.S. pharmacists who’ve worked with them before.

The Hidden Threat: Authorized Generics

The biggest risk to a first-mover isn’t another generic company. It’s the brand-name drugmaker itself. Many brand companies launch an “Authorized Generic”-a version of their own drug, sold under a generic label, during the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity window. The FTC found this practice reduces the first-mover’s retail prices by 4-8% and wholesale prices by 7-14%. Suddenly, instead of a duopoly (brand vs. generic), you have a three-way battle: brand, first generic, and authorized generic. In these cases, the first-mover’s advantage shrinks dramatically. Some companies lose over 50% of their projected revenue. That’s why top generic manufacturers now build contingency plans: securing backup API suppliers, negotiating bulk discounts (often 12-15% cheaper than later entrants), and sometimes even partnering with the brand to get access to their distribution network.It’s Not Just About Price

Most people assume generics compete on price alone. But in reality, the first-mover wins because of access, not just cost. Pharmacies stock only one version of each generic drug to reduce inventory complexity. Once they’ve chosen a supplier, they rarely change-unless forced by a payer or if the product runs out. First-movers get that slot. They also get preferred placement on formularies, better rebate deals from insurers, and automatic substitution at the pharmacy counter. Even more telling: companies that expand their generic’s approved uses faster than competitors gain a 13-point market-share edge. Why? Because doctors start prescribing it for more conditions. The more uses it has, the more likely it becomes the default choice.

What’s Changing in the Game

The rules are shifting. The FTC has cracked down on “pay-for-delay” deals-where brand companies pay generics to delay entry. Since 2023, these deals have dropped by 60%, and first generics are now entering the market 6-9 months earlier on average. Meanwhile, complex generics-like inhalers, eye drops, and injectables-are becoming the new battleground. These drugs are harder to copy. Fewer companies can make them. That means fewer competitors. And that means first-mover advantages are stronger than ever: 15-20 percentage points above fair share, compared to just 6-8 for simple pills. But there’s a counter-trend. The FDA is releasing more guidance documents to standardize how complex generics are developed. That’s lowering the knowledge barrier. Over time, that could mean more entrants-and less dominance for the first.What This Means for the Future

The first-mover advantage in generics isn’t going away. Even as more companies enter the market, the core drivers remain: prescriber habits, pharmacy stocking rules, and patient inertia. These aren’t easy to change. The data is clear: the first generic doesn’t just get a head start. It gets a lock on the market. By the time competitors arrive, the first mover is already the default. And in healthcare, default means dominance. Companies that want to win need more than a patent challenge. They need a supply chain that can scale, a regulatory team that knows the FDA inside out, and a sales strategy that gets the drug into every pharmacy before the second entrant even files. Because in this game, being first doesn’t just give you a chance to win. It gives you the entire field.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it help generic manufacturers?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a legal framework that lets generic drug makers challenge brand-name patents while still protecting the brand’s innovation incentives. The key benefit for generics is 180 days of exclusive marketing rights if they’re the first to file a patent challenge and win. This exclusivity lets them capture the majority of the market before competitors enter, giving them pricing power and strong customer retention.

Why do pharmacists stick with one generic version instead of switching to cheaper ones?

Pharmacists typically stock only one version of a generic drug to simplify inventory management and reduce errors. Once a pharmacy chooses a supplier, they rarely switch unless forced by a payer or if the product is out of stock. The first generic to enter usually secures that slot, making it the default option for patients-even if a cheaper version becomes available later.

What is an Authorized Generic and why is it a threat to first-movers?

An Authorized Generic is a version of the brand-name drug sold under a generic label, often by the original manufacturer. When launched during the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity period, it creates a three-way competition: brand, first generic, and authorized generic. This can slash the first-mover’s prices by 4-14% and cut revenue by up to half, turning what should be a monopoly into a crowded market.

Do large generic companies have a bigger advantage than small ones?

Yes. Large companies with existing generic divisions, multiple API suppliers, and FDA-experienced teams capture 10+ percentage points more market share than smaller first-movers. They can scale production faster, negotiate better supplier deals, and have sales teams that convince doctors to switch. Small companies often win the filing race but lose the market share battle.

Why are complex generics like injectables and inhalers better for first-movers?

Complex generics are harder and more expensive to develop. Fewer companies can make them, so competition is limited. This means the first entrant faces fewer rivals and can dominate the market with 15-20 percentage points above fair share-much higher than the 6-8 points seen in simple oral pills. The technical barrier protects their position longer.

Will the first-mover advantage disappear as more companies enter the generic market?

No-not yet. Even with more competitors, the core drivers remain: prescriber habits, pharmacy stocking rules, and patient loyalty. First-movers still capture 30-40% of the market even after five or more generics enter. Second entrants rarely get past 15%. The system is built to favor the first, and that’s not changing anytime soon.

11 Comments

Webster Bull December 11 2025

This is wild. Being first isn't just an edge-it's a goddamn fortress. Pharmacies don't switch because they're lazy, not because the drug is better. System inertia is real, and it's rigged.

Bruno Janssen December 11 2025

I just read this and felt nothing. Too much data. Too many numbers. Makes my head hurt.

Tommy Watson December 12 2025

Authorized generics are the ultimate betrayal. Brand companies are like, 'Hey we made this drug, now we're selling it cheaper under a fake name??' That's not capitalism, that's psychological warfare. 😭

Donna Hammond December 12 2025

The real takeaway here is that healthcare systems reward familiarity over efficiency. Patients aren't loyal to the drug-they're loyal to the routine. That’s why switching costs matter more than price. This isn't a market failure. It's a behavioral one.

Karen Mccullouch December 12 2025

US manufacturers win because they're American. Period. Foreign generics? They get delayed at customs, their quality's sketchy, and pharmacists don't trust 'em. America First in generics too. 🇺🇸

Lauren Scrima December 14 2025

So... we're saying the system is designed to reward the slowest? The first one to file gets rich, even if they can't deliver? That's not innovation. That's a lottery ticket with a pharmacy chain as the prize.

sharon soila December 16 2025

Everyone deserves affordable medicine. But if we want real change, we need to fix the system-not just cheer for the first one to win. It's not about speed. It's about fairness.

nina nakamura December 16 2025

The data is garbage. McKinsey? DrugPatentWatch? These are industry shills. Real market share data is hidden behind NDAs. You think they'd let some blog post see the full picture? Lol.

Hamza Laassili December 18 2025

I mean… why do we even let this happen? The FDA is supposed to protect us, not help big pharma rig the game. First-mover? More like first-scam. This is why meds cost so much.

Rawlson King December 19 2025

This is why Canada's system works better. No 180-day exclusivity. No authorized generics. Everyone gets the same price. Simple. Efficient. No corporate theatre.

Constantine Vigderman December 20 2025

I love this so much!! 🤩 First-mover = king of the hill. And the best part? The system keeps them there. Even when cheaper options show up, people don't switch. It's like the drug version of sticking with Windows because you're scared to learn Linux 😅